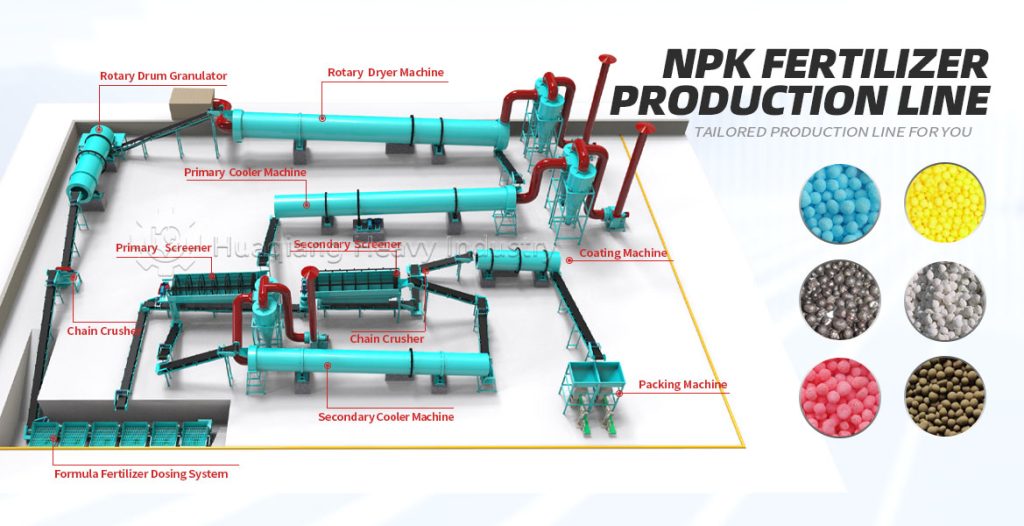

As an indispensable high-efficiency fertilizer in agricultural production, the production process of NPK compound fertilizer is a precisely controlled and interconnected system engineering project. The core is the scientific proportioning of nitrogen (N), phosphorus (P), potassium (K), and various auxiliary materials, processed through multiple processes into a finished product with uniform granules and stable fertilizer efficacy. The entire NPK fertilizer production line balances efficiency and quality, adhering to strict process standards throughout to ensure balanced fertilizer nutrients that meet agricultural needs.

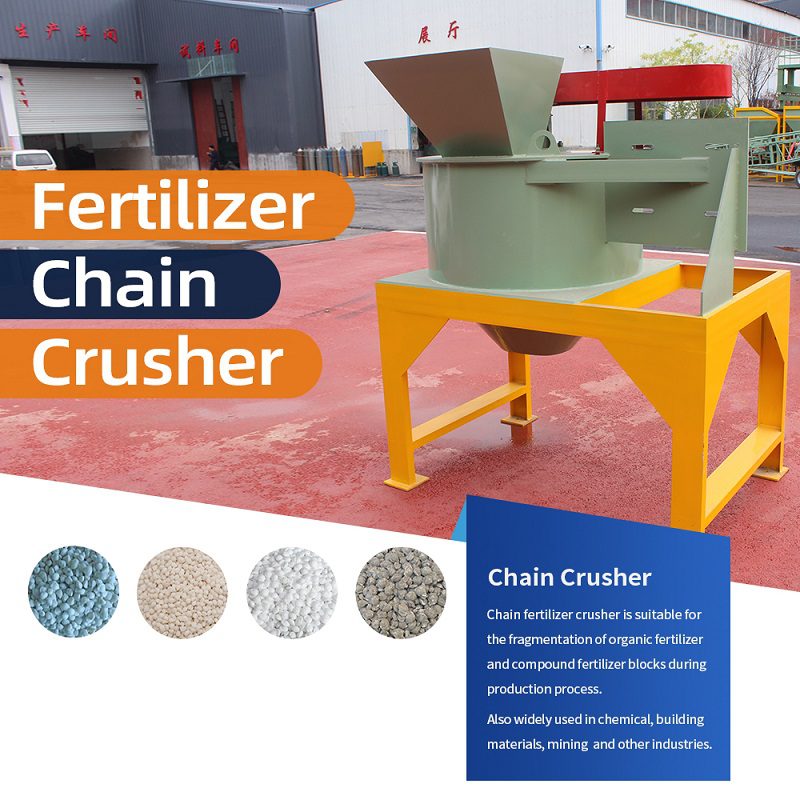

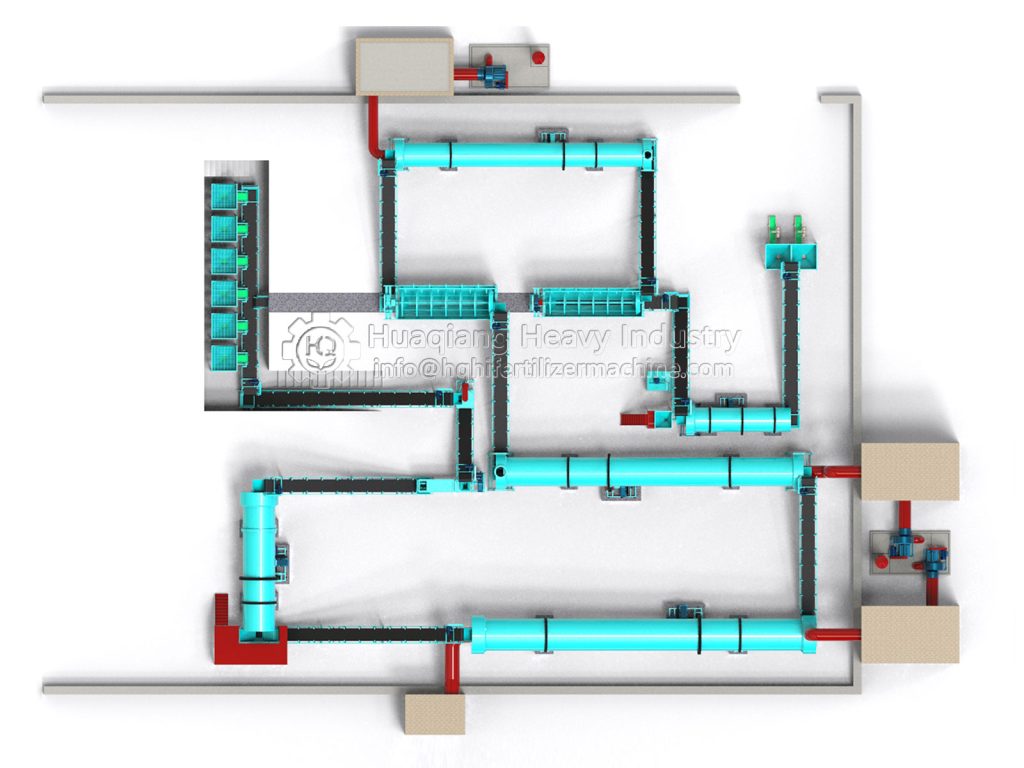

The first step in production is raw material pretreatment and precise batching. Raw materials must meet standards. Nitrogen sources often use ammonium nitrate phosphate, phosphorus sources use highly water-soluble ammonium dihydrogen phosphate, and potassium sources use potassium sulfate or potassium chloride. Calcium compounds and other auxiliary materials can be added to enhance fertilizer efficacy. Workers first crush and sieve the raw materials to remove impurities and refine the particles. Then, according to the product formula requirements, an automatic batching system precisely weighs the materials according to the proportions, ensuring that the ratio of nitrogen, phosphorus, potassium, and auxiliary materials is controlled within a reasonable range, laying the foundation for subsequent production.

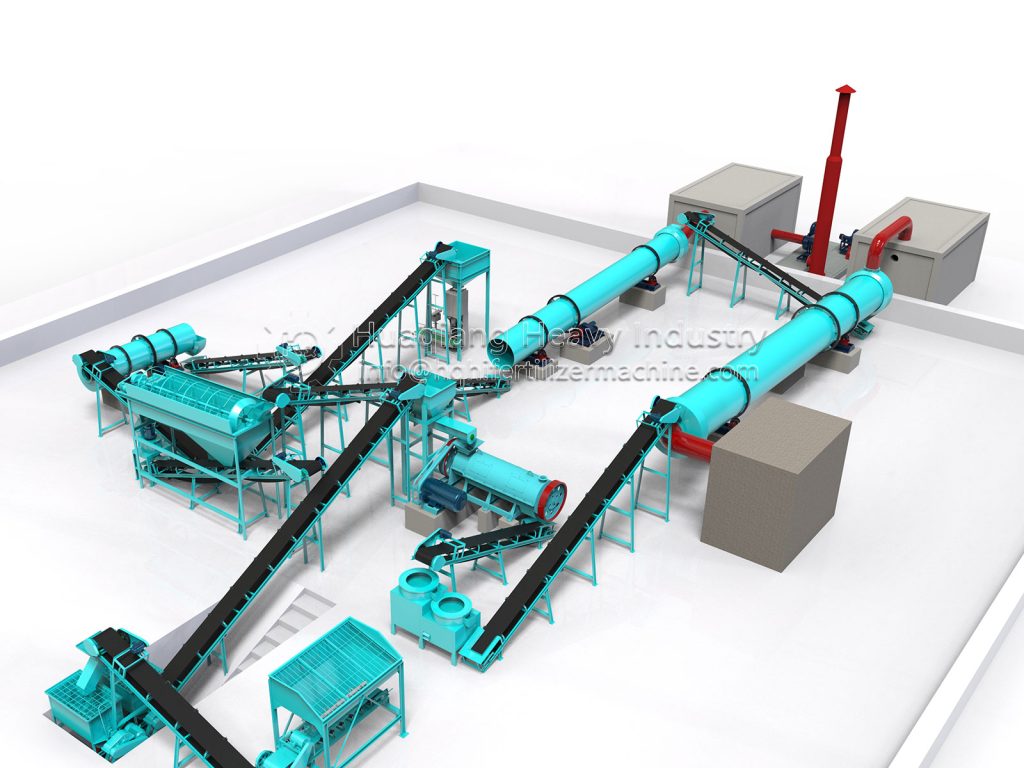

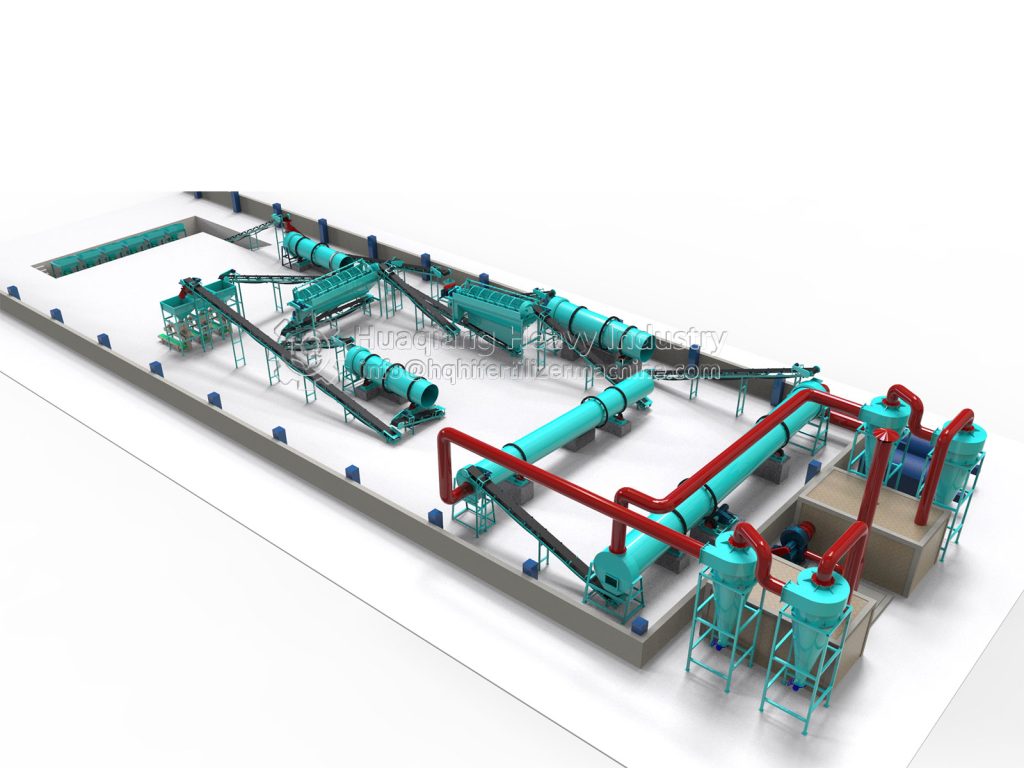

After the ingredients are mixed, they directly enter the granulation stage, a crucial step that determines the product’s form. Currently, the mainstream methods employ wet granulation processes such as rotary drum granulation and disc granulation. In the granulator, the material undergoes physical extrusion or agglomeration, combining with an appropriate amount of moisture to form uniform particles. Some high-end production lines utilize tubular reactor technology, atomizing and spraying high-temperature slurry onto the granulator bed for coating and granulation, which can improve water-soluble phosphorus utilization and reduce energy consumption.

The granulated wet particles need to undergo drying, cooling, and sieving. The wet particles are fed into a dryer to remove excess moisture. After cooling, they are sieved to separate qualified particles from unqualified powder and large particles. Unqualified materials are crushed and re-granulated, achieving resource recycling. Qualified particles after sieving can undergo coating treatment, adding conditioning agents to improve anti-caking performance, and then enter the finished product testing stage. Nutrient content, particle size, moisture content, and other indicators are tested according to national standards to ensure product quality.

Finally, packaging and storage are carried out. The qualified granules are quantitatively packaged and sealed by an automated packaging machine, labeled with product specifications, nutrient content, and other information, and then sent to a dedicated storage area to prevent moisture and clumping. The entire NPK production line achieves automated and standardized operation, which not only ensures the quality stability of NPK compound fertilizer but also improves production efficiency, providing a reliable fertilizer guarantee for agricultural harvests.